Kirkwood history, continued

Part of the ‘Smith family history’ series

Part of the ‘Kirkwood history’ series

In the interest of not straying too far away from the Smith family, I’m going to mention a few more comments about Kirkwood history at this time, then refocus back on Robert Windsor Smith and his family.

From the late 1860’s and throughout the 1870’s, Kirkwood remained a mostly rural country village, apparently desirable to many of Atlanta’s political elite as we’ve seen mentioned in the previous post. The availability of an “accommodation train” that ran on the Georgia Railroad between Atlanta and Decatur was beneficial to those who were doing business in Atlanta, but preferred a more suburban, and white, enclave.

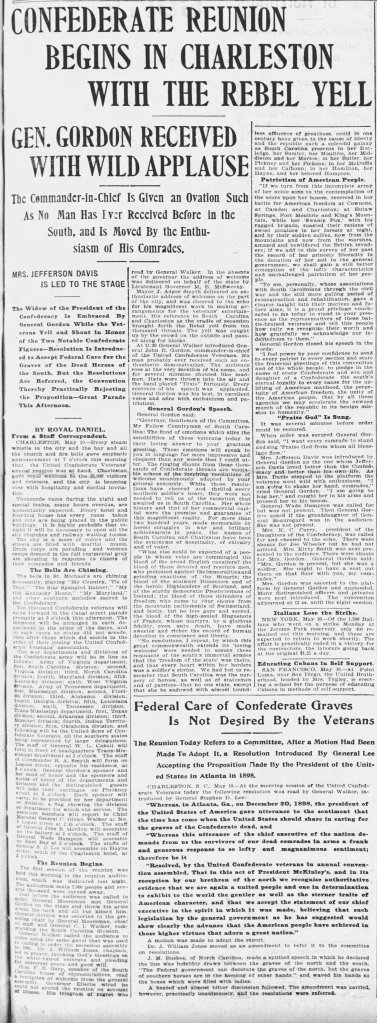

While the article above paints a bucolic portrait of this “little village,” it’s important to keep in mind that the political tactics of many of the prominent “redeemer” citizens of Kirkwood mentioned above were undeniably racist. They undoubtedly benefited from convict lease programs, legislative measures like the poll tax intended to deliberately disenfranchise (male) black voters, the Klan’s intimidation through violence, and the enshrinement of the Confederate “Lost Cause” mythos. John B. Gordon, in particular, seems to have embodied this nostalgia for the Confederacy as we can see in this 1899 article about a visit he made to Charleston, S. C. for a Confederate “reunion.”

On the surface, this celebration of Gordon and the Confederacy may seem like an innocuous remembrance. However, an earlier speech that Gordon gave to a Charleston, S.C. crowd in 1868 included what sounds more like an outright threat…

Now I speak plainly. If you are disposed to live in peace with the white people they extend to you the hand of friendship. But if you attempt to inaugurate a war of races you will be exterminated. The Saxon race was never created by Almighty God to be ruled by the African. These are truths. We want peace with you. We cannot live as enemies. One or the other must go down. If you turn a deaf ear to the Southern man, these green leaves that now clothe the forest will not grow red with another autumn before they will be drenched with your blood and mine.

Charleston Daily Courier, 9/12/1868

As I previously mentioned, John B. Gordon was not only a U. S. senator from Georgia (twice: 1873-1880 & 1891-1897), the governor of Georgia from 1886 to 1890, but also the supposed head of the Klan in Georgia, at least for some period of time after the war. Gordon had lost the 1868 gubernatorial election to Republican Rufus Bullock, and on July 27th, 1871 testified to Congress in Washington D. C. about (amongst other things) his involvement with the Klan.

Question. What do you know of any combinations in Georgia, known as Ku-Klux, or by any other name, who have been violating law?

Answer. I do not know anything about any Ku-Klux organization, as the papers talk about it. I have never heard of anything of that sort except in the papers and by general report; but I do know that an organization did exist in Georgia at one time. I know that in 1868—I think that was the time — I was approached and asked to attach myself to a secret organization in Georgia. I was approached by some of the very best citizens of the State — some of the most peaceable, law-abiding men, men of large property, who had large interests in the State. The object of this organization was explained to me at the time by these parties; and I want to say that I approved of it most heartily. I would approve again of a similar organization, under the same state of circumstances.

Question. Tell us all about what that organization was.

Answer. The organization was simply this — nothing more and nothing less: it was an organization, a brotherhood of the property-holders, the peaceable, law-abiding citizens of the State, for self-protection. The instinct of self-protection prompted that organization; the sense of insecurity and danger, particularly in those neighborhoods where the negro population largely predominated.

John B. Gordon testimony to Joint Select Committee on the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States

Gordon also seems to imply that fellow Kirkwood resident Alfred H. Colquitt would know “as much information as anybody else in our state” with regards to “the organization.” Colquitt would later serve alongside Gordon in the U. S. Senate, as well as Governor from 1877 to 1882.

The fact is that, in my judgment, the organization was a very temporary thing; I do not think it existed any length of time at all; I do not think it was ever even perfected. I have given you just the intention of the thing as I understood it. I never heard anything more about it after that until I talked with General Colquitt, just before leaving Atlanta, to come here. He had not heard anything about it for a long time. It was simply understood among the members of this organization that if the necessity should arise, we would unite to put down disturbance, and that we would extend the organization if required.

John B. Gordon testimony to Joint Select Committee on the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States

It’s important to understand that this testimony took place after the Enforcement Acts of 1870 & 1871 had already been enacted, including the Civil Rights act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act. Given that context, and the inherent secrecy of “the organization”, it’s not surprising that Gordon would attempt to either distance himself from it, or characterize it as a “peace police organization.” Enforcement of the Klan Act led to prosecution and jailing of Klansmen in South Carolina, and by 1872 “the organization” seemed to have been eradicated.

One of Gordon’s neighbors in Kirkwood was his acquaintance Dr. Alfred F. Green. Green had settled in Kirkwood sometime around 1889-1890, following his brother Elijah W. Green’s move there around 1887-1888. Alfred Green had married Miss Annie Kate Taylor (later remarried and commonly referred to as Kate Green-Hess) on Halloween in 1885, and once they arrived in Kirkwood built an expansive home on Howard Street just across the Georgia Railroad tracks from Gordon. The house still stands today, a stones throw from my own home.

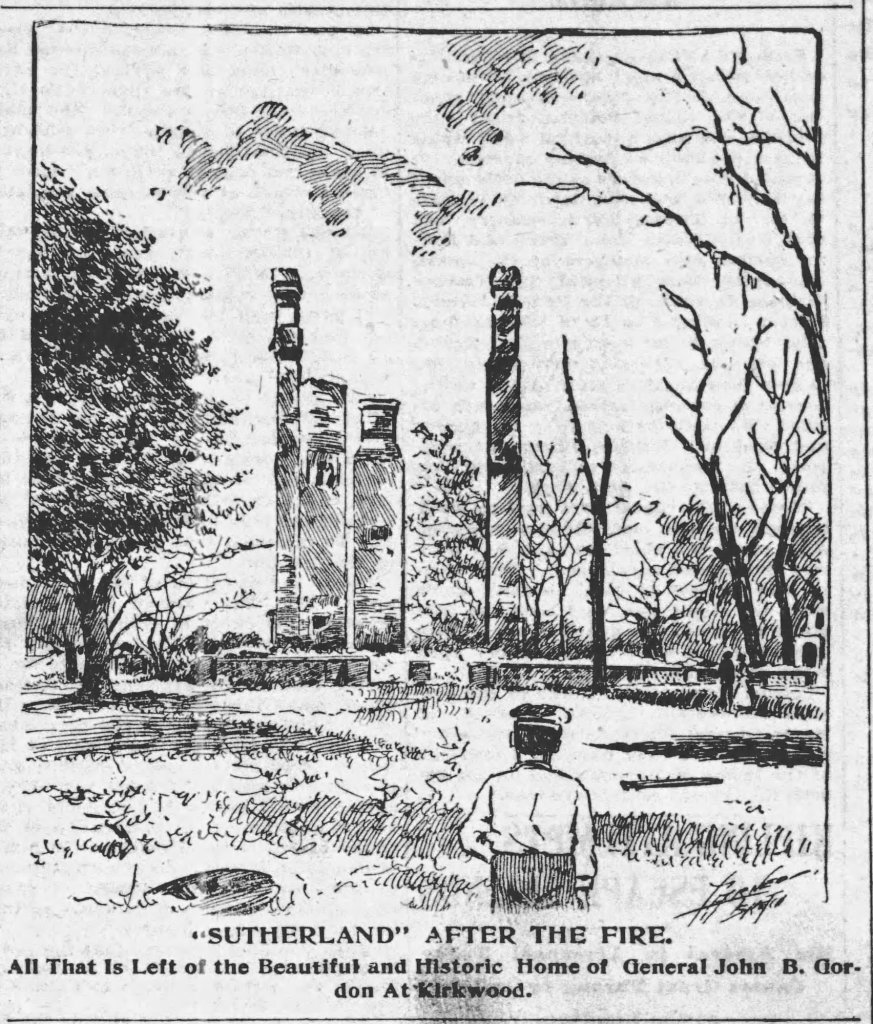

John B. Gordon’s “Sutherland” estate was not so lucky. The original Sutherland burned to the ground on Wednesday, June 21st 1899. Gordon himself was out of town, but family, friends, and neighbors (including Dr. Alfred F. Green) hurriedly removed as much of the contents of the home as possible to prevent them from being lost to the fire. Note, that the image of Sutherland presented in my previous post is the Greek Revival house built after the original had burned. That second iteration of Sutherland stood until sometime between 1938 and 1949 (photos exist from 1938, gone in 1949 aerial photography).

UPDATE – Gordon’s rebuilt Greek Revival house was demolished in October of 1942.

Unfortunately for Dr. Alfred F. Green, he became ill (I would imagine due to smoke inhalation) following his efforts to help save the contents of Gordon’s home, and he passed away a few days following the fire on June 29, 1899. Dr. Green left behind children from a previous marriage, as well as several he had been raising with Kate in their beautiful home there on Howard Street in Kirkwood. More on one of those children in a moment…

Following John B. Gordon’s death in 1904, the 1905 publication of Thomas Dixon Jr.’s The Clansman, the subsequent stage production of The Clansman (which D. W. Griffith based The Birth of a Nation on), and the horrific 1906 Atlanta race massacre, a statue of Gordon astride a horse honoring the Confederate “hero” was installed at the Georgia state capitol in 1907 where it remains today.

Prior to the installation of the Gordon statue at the capitol, Mrs. Kate Robson (who you may recall from my last post is credited with giving Kirkwood its name) collected ribbons from Gordon’s gravesite and sewed them into a Confederate banner which was gifted to his widow. Interestingly, the March 8, 1904 article describing this mentions that Robson had also “made the flag under which General Gordon first left for the war in 1861 as captain of the infamous Raccoon Roughs.“

The year following the installation of the Gordon statue on the capitol grounds, in April of 1908, a granite obelisk was erected in Decatur (Kirkwood’s easterly neighbor) memorializing Confederate soldiers. An article printed in the Atlanta Journal the day before it was unveiled stated the following:

It is hoped that the day is near at hand when such a monument will rise in every city and hamlet in the south as an enduring witness of the glory which clusters about the Lost Cause.

Atlanta Journal, 4/24/1908

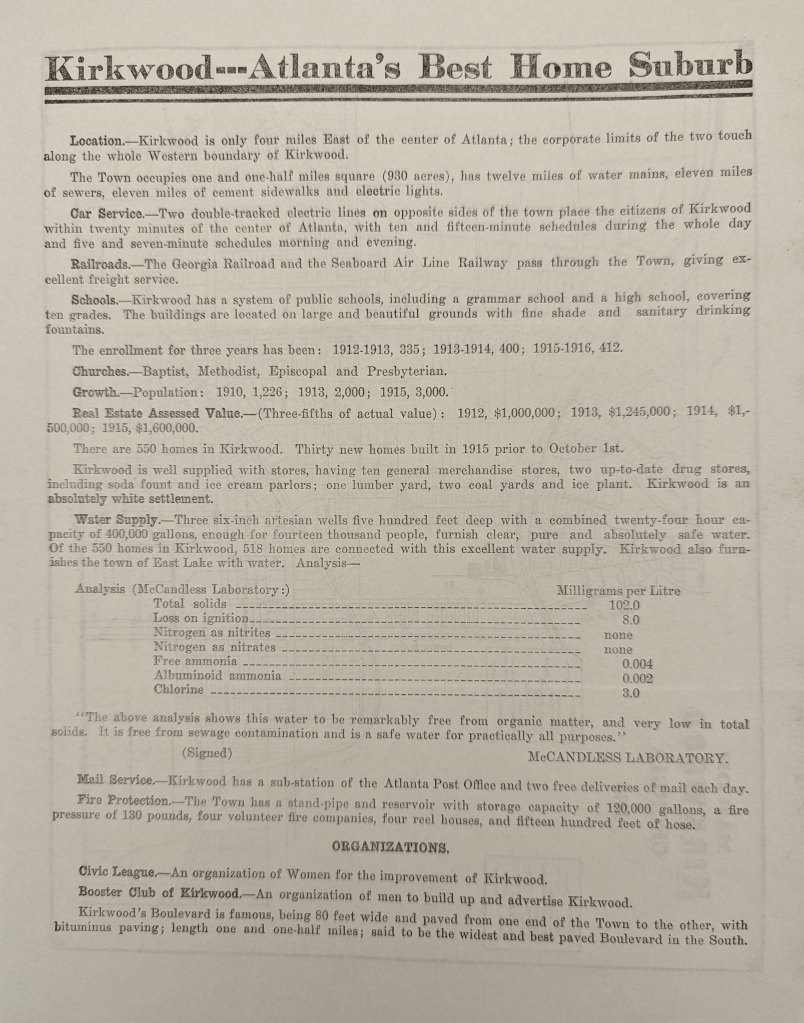

Unfortunately, the foundation of white supremacy in Kirkwood extended well past the turn of the century. Note the bolded text near the middle of the page on this January 1916 flyer espousing the qualities of pre-annexation Kirkwood: “Kirkwood is an absolutely white settlement.“

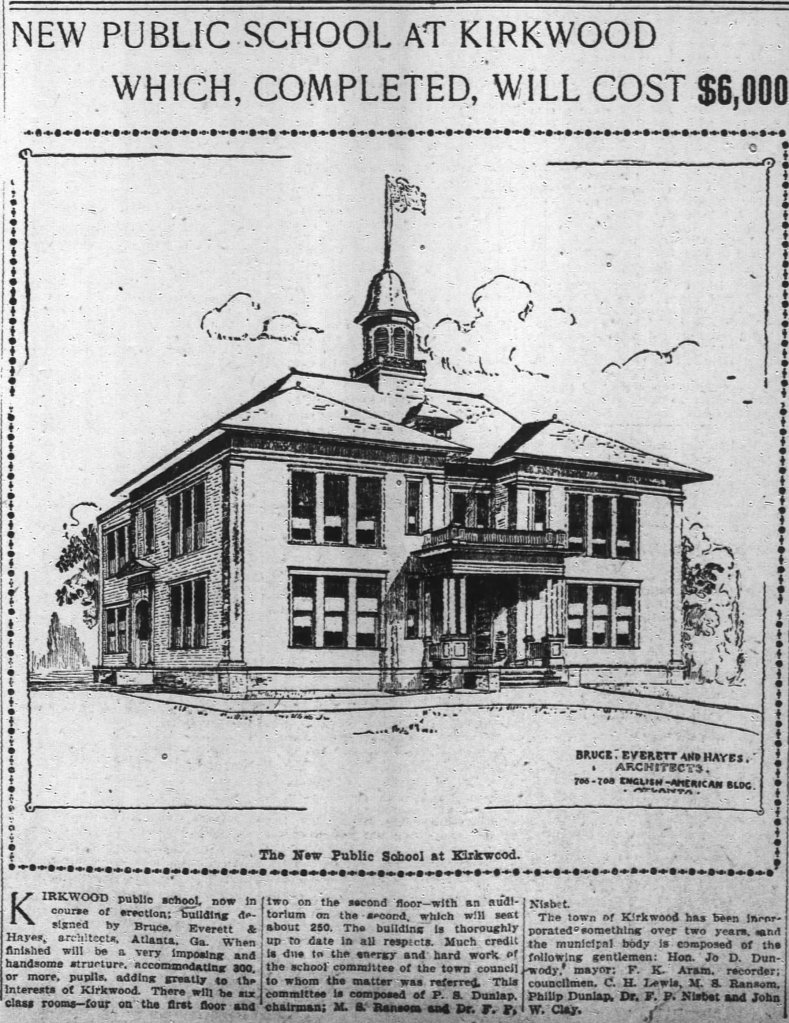

Amongst the amenities listed on the 1916 advertisement for Kirkwood is a reference to Kirkwood’s schools. The first school was built in 1906, following the successful 1904 incorporation, and on September 10, 1906 104 (presumably all white) pupils were in attendance. We’ll come back to the school in a moment as well…

The fact that the 1916 flyer boasts Kirkwood’s “absolutely white” population as worthy of inclusion in an advertisement is not surprising given the state of Jim Crow-era Atlanta at this time. As someone who has invested an inordinate amount of time poring over Atlanta area newspapers from around this period, disturbing patterns emerge, specifically that of the repeated claims of “the ravishing of white women by black brutes.” Thomas Dixon Jr.’s The Clansman (which included the fictional rape of a 15 year-old white girl by a former slave) is probably to blame for much of this, and the 1906 Atlanta race massacre was sparked by newspaper articles alleging four attacks on white women.

Thomas E. Watson‘s newspaper “The Jeffersonian” stands out as being particularly sensationalistic in this regard, bordering on grotesque. However, in addition to peddling white supremacist tropes stereotypical of the time, Watson’s paper began to take a decidedly antisemitic tone following the April 26, 1913 murder of Mary Phagan. Mary Phagan was a 13 year-old girl who had worked in the National Pencil Company in Atlanta, employed by a young Jewish northerner named Leo Frank who had lived in Atlanta since 1908. In the interest of time, I’ll provide a very brief list of relevant events to help readers understand the context here…

- April 26, 1913 – Mary Phagan is murdered and her body is discovered the next day in the basement of the National Pencil Factory. Leo Frank is arrested shortly thereafter despite the lack of any conclusive evidence.

- August 25, 1913 – Leo Frank is convicted of the crime and the following day is sentenced to death by hanging.

- December 1913 – April 1915 – Following his conviction, Leo Frank’s case is unsuccessfully appealed to the Georgia Supreme Court, and then ultimately to the U. S. Supreme Court.

- June 21, 1915 – Leo Frank’s death sentence is commuted to life in prison by Georgia Governor John Slaton. Slaton would leave office and the state of Georgia shortly after and did not return for over a decade.

- ~June 26, 1915 – The “Knights of Mary Phagan” organize at her gravesite in Marietta and vow to “never rest til the murder is avenged.”

- August 16-17, 1915 – A group of vigilantes abduct Leo Frank from prison in Milledgeville and drive him to Marietta where he is lynched, hung from an oak tree facing the direction of Mary Phagan’s home. One of the key figures of the lynch mob is former Georgia Governor Joseph Mackey Brown, son of Governor Joseph E. Brown, an associate of John B. Gordon and part of the Bourbon Triumvirate alongside him and Colquitt.

In response to public criticism of the lynching from Northern state newspapers and local institutions such as the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce, Thomas Watson threatens in his journal:

[If they don’t] quit meddling with our business, increasing offices, raising taxes, and getting pardons and commutations for assassins, poisoners, and rapists who have a “pull,” another Ku Klux Klan may be organized to restore HOME RULE.

The Jeffersonian, 9/2/1915

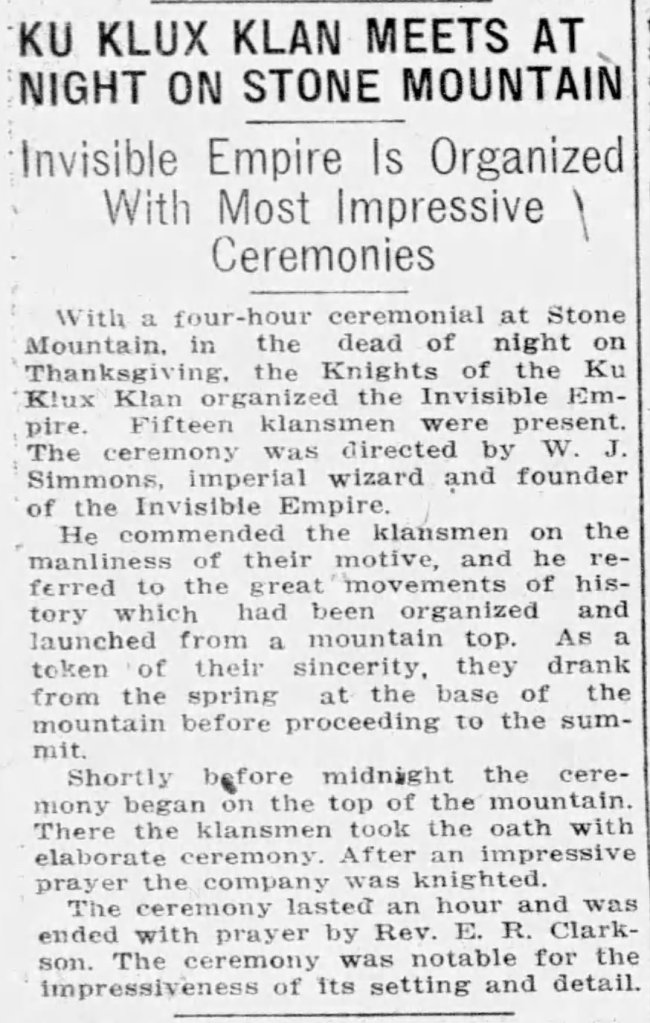

A small note appears in the legal notices section of the November 1, 1915 Atlanta Journal regarding formation of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, referred to as a “fraternal beneficiary society.” On the night of Thanksgiving, November 25, 1915, William Joseph Simmons holds a ceremony atop Stone Mountain where a cross is burned and the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan is born.

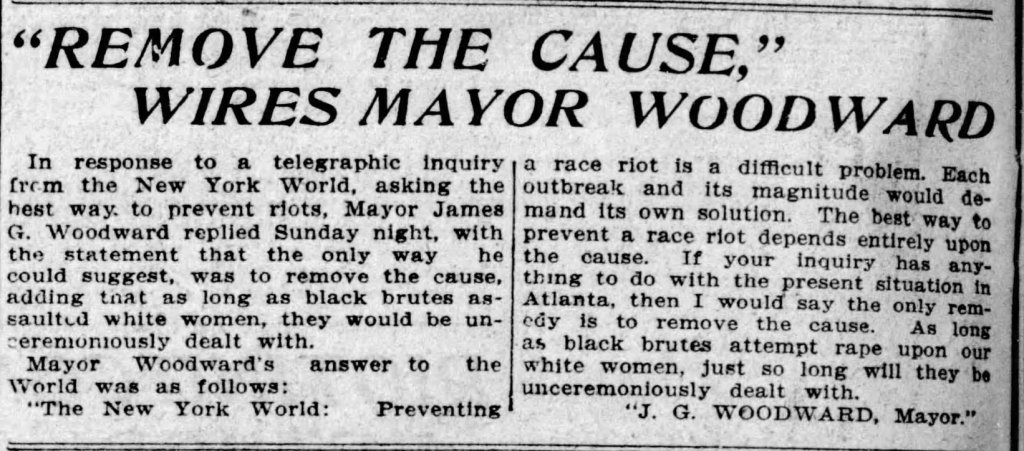

A little over a week later, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation opens at the Atlanta Theater to great fanfare. While the film represents an important milestone in the history of cinema it is also (particularly in the second half) shamefully racist. Not only does the film reinforce the stereotype of the danger of “brutes” attacking and defiling white women, it props up the Ku Klux Klan as protectors and saviors that defended the south from reconstruction. A committee of local ministers had appealed to Mayor James Woodward months earlier to prevent the screening of the film in Atlanta out of concern that it “might stir up race prejudice.” It’s not difficult to understand why Woodward was disinclined to seriously consider their appeal when you realize that his response to the 1906 Atlanta race massacre (which took place during his earlier tenure as Mayor) was as follows:

Let’s return now to one of Dr. Alfred F. and Kate Green’s children, Samuel Green. Dr. Samuel Green was born in 1889 and was raised in their elaborate home on Howard Street (once construction had completed in the mid-1890’s). Green graduated from Emory and was a practicing obstetrician. He was also a prominent Klansman, joining in 1918. Around this time Klan membership had swelled to upwards of 4,000,000, and Georgia led the nation in the number of lynchings from 1900 to 1931 [302]. The pinnacle of racial violence in U.S. history occurred during this period, when in 1921 an alleged assault on a white woman by a young black man in my hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma led to the Tulsa race massacre.

A widely publicized 1925 conviction of Klansman D. C. Stephenson and The Great depression led to a significant decline in Klan membership. Samuel Green was promoted to Grand Dragon of Georgia in 1929 following Nathan Bedford Forrest II‘s promotion to “Imperial Klokann.” As a celebration of his first anniversary of service as Grand Dragon of Georgia, Green was presented with an engraved watch.

Klan membership continued to decline and by 1939 Imperial Wizard Evans sold the organization to Green and an associate. In 1944 the I.R.S. attempted to recover over half a million dollars from the organization which led to its dissolution.

After World War II Green reformed the Klan at a ceremony atop Stone Mountain and eventually was named to the highest position of Imperial Wizard. Familiar tactics of voter suppression through the threat of violence were employed, as can be seen in this March 1948 article:

While I won’t repeat the language Green used here, I would strongly encourage my readers to have a look at this 1946 article on Green published in Cosmopolitan magazine to truly understand what kind of person he was. Green died on August 18, 1949. Following his death, there were apparently plans for an “elaborate monument,” but from what I can tell that did not come to pass.

One of the ugliest manifestations of the lingering racism brewing under the surface of “Atlanta’s best home suburb” is what occurred at Kirkwood Elementary School when Atlanta Public Schools forcibly integrated the school in January of 1965. APS had begun integration of their schools in 1961, starting with high schools, and planned to integrate one grade level per year. President John F. Kennedy praised Atlanta’s efforts at the time:

I strongly urge the officials and citizens of all communities which face this difficult transition in the coming weeks and months to look closely at what Atlanta has done, and to meet their responsibilities as have the officials and citizens of Atlanta and Georgia, with courage, tolerance, and above all, respect for the law.

John F. Kennedy, 8/31/1961

In December of 1964, Kirkwood Elementary had approximately 450 white students enrolled, which was already a reduction from it’s earlier enrollment and was well under its capacity of 1,000. Meanwhile, most of the “black” schools in the area were severely overcrowded. A confrontation between an NAACP leader and school officials led to his arrest at the beginning of the 1964 school year. APS then created an “annex” in a nearby church, which resulted in boycotts and picketing by parents. This pressure apparently resulted in a decision to integrate Kirkwood’s school sooner than later.

The Atlanta Constitution reported that on Monday, January 25, 1965 approximately 500 black children were enrolled at Kirkwood Elementary, and of the 470 white children enrolled there the previous month only 7 remained. The entire teaching staff left with the white students, and only the white principal remained at the school.

Many white families, anticipating the integration of the school (and the neighborhood), had already moved away and soon many more would leave in a textbook case of “white flight,” radically changing the demographics of the neighborhood within a matter of a few years. The neighborhood would eventually become more racially diverse and gentrified over time, bringing a new set of challenges for long-term residents, regardless of race.

So what do we make of all of this? My intention here isn’t to pick at old wounds, and I don’t profess to know the truth of people’s hearts from 150 years ago, 100 years ago, 50 years ago, or now for that matter. On the one hand it seems easy to cast judgement in the case of the Kirkwood school integration and related white flight… But ask yourself what you would do if the friends and families you had known in your community, that had in some cases been there for multiple generations, suddenly started to leave?

The pressure from blockbusting must have been intense, and many of the churches (undoubtedly cornerstones of the community at the time) had begun to exit Kirkwood at this time as well. The last Smith family resident living in Kirkwood proper (not taking into account “north” Kirkwood, now the Lake Claire neighborhood) was Dorothy Miles. Dorothy was Robert Windsor and Mary Smith’s granddaughter, her mother was Spencer Hill. Dorothy and her husband Carl Miles lived in Robert and Mary’s home at 172 Howard Street from at least 1950 until his death in 1958. Dorothy stayed there until sometime in 1964 or 1965 when at the age of 61 she moved elsewhere.

Regarding Samuel Green… There is an irony here that simply can’t be ignored. What is arguably the most beautiful old home in Kirkwood today was also the childhood home of one of the ugliest people to ever live here. Can we easily separate the aesthetic and historic value of a home from the history of the people who lived there? I would argue you can, and the value of the architecture as an example of the period is worthy of appreciation and preservation.

However, there is also value in the family history as well, regardless of the discomfort it inevitably leads to. It makes you wonder… what were the circumstances, what words were spoken, what kind of people lived in that place, that raised a child to become an Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan? What role did the connection with John B. Gordon play, that when Green was but 10 years old, his father perished trying to save furniture from this symbolic person’s home? What value must have been assigned to such a symbol that this sacrifice was warranted?

Which brings us to this question of monuments, and what they represented then and now. The power and impact of symbols and monuments, particularly as put forth in public spaces cannot, in my opinion, be discounted in the slightest. The state of Georgia’s track record in adequately addressing these symbols is poor. Some examples in a regional and certainly incomplete list…

- The current Georgia flag is based on the first Confederate flag, aka “The Stars and Bars.”

- Georgia Capitol grounds monuments (including the adjacent Georgia Plaza):

- John B. Gordon statue – 1907

- Joseph E. Brown statue – 1928

- Thomas E. Watson statue – 1932

- Eugene Talmadge statue – 1949

- Stone Mountain Confederate memorial carving – This is really just too much for me to even begin to delve into here, BUT I strongly suggest watching the Atlanta History Center’s outstanding 30 minute documentary “Monument: The Untold Story of Stone Mountain.“

The prospect of removing these symbols is unfortunately always controversial. On the one hand, without the reminders of this ugliness maybe it becomes too easy to forget. On the other, I cannot imagine what it must be like for black people to have these ever-present symbols of white supremacy in public spaces, and to know that there will continue to be forces willing to fight to preserve them. The rationale for preservation in some cases might be a sincere desire to maintain some kind of historical context, but doing so also protects these monuments as racist rallying points, as we saw with the 2017 “Unite the Right rally.“

Regarding the Confederate obelisk installed in Decatur in 1908, it was removed in 2020 and as of August 16, 2024 a statue of John Lewis stands in its place. I haven’t been over to Decatur to see it yet, but I’m perfectly happy with the change. While the specter of the Klan tugged at some of the most base human prejudicial instincts, I think it’s evident that in many ways it was an organization concerned foremost with political power that leveraged racist intimidation tactics as a means to its ultimate desired goal of voter suppression. What better symbol in opposition to voter suppression could there be than John Lewis?

The idea of “home” is a funny thing in some ways. We generally tend to think of it as a place within a spatial sense, but less frequently within a temporal one. I think many young families move somewhere without really understanding much of the specific history of that place. I certainly didn’t know anything about Kirkwood history before we purchased our first home here. It ultimately becomes a question of scale, and how much of the picture you can see and begin to understand and come to your own conclusions about that history.

I believe that in that understanding of history we can develop a deeper care for our home in the present. Even when unfortunate aspects of that history repulses us. I’m reminded of that on a nearly daily basis as I walk past Samuel Green’s boyhood home, or the Kirkwood Elementary school (converted now to residential lofts). I suppose it goes without saying (although I’ll say it anyway) that matters of race in the United States, and particularly in the South, are way too complicated of an issue for me to even begin to meaningfully address in my little blog about the place I live. However, I, and any other Kirkwood residents, would be remiss to ignore the history of our home.